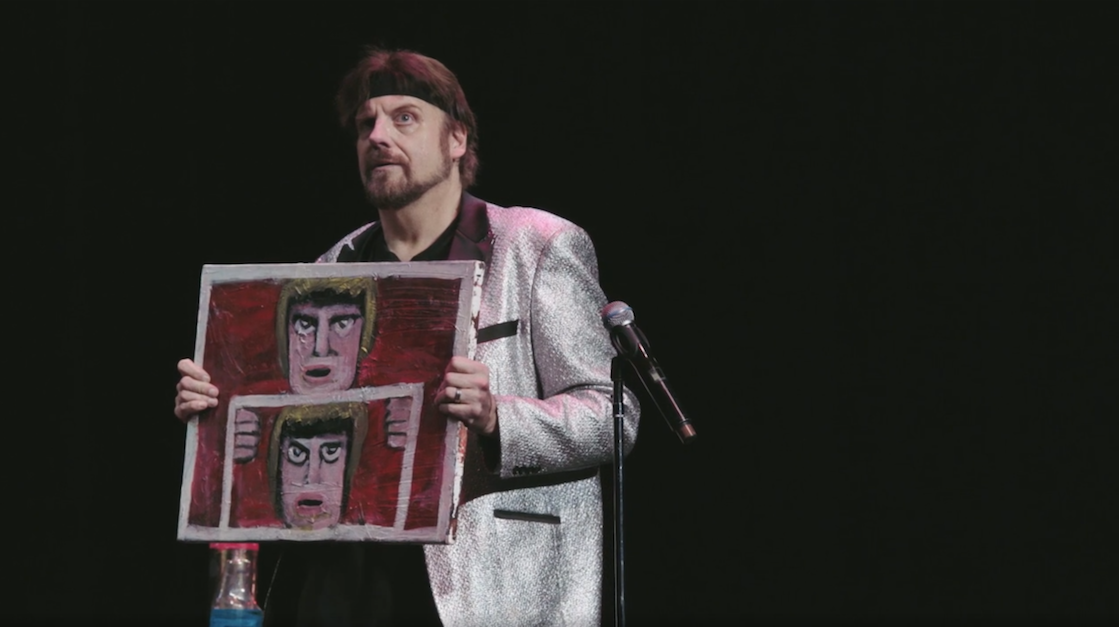

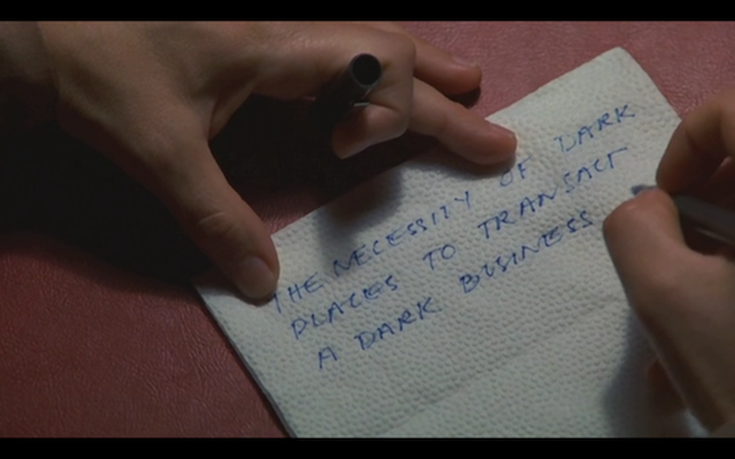

Rohrwacher's La Chimera (2023), currently in UK cinemas, features stunning descents into old Etruscan tombs in Tuscany, to plunder old artifacts.

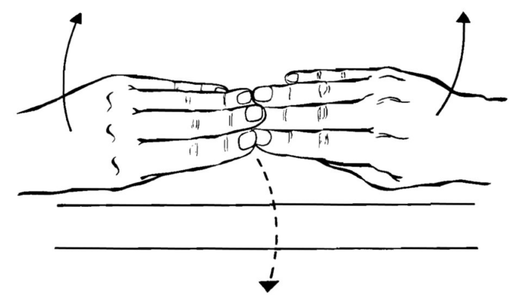

The film has rightly been described as 'folk magic' for the way it charts the main character's uncanny journey between the living and the dead, complete with the use of dowsing to sense where a tomb might be underfoot. I would add there's something fable-like at play too.

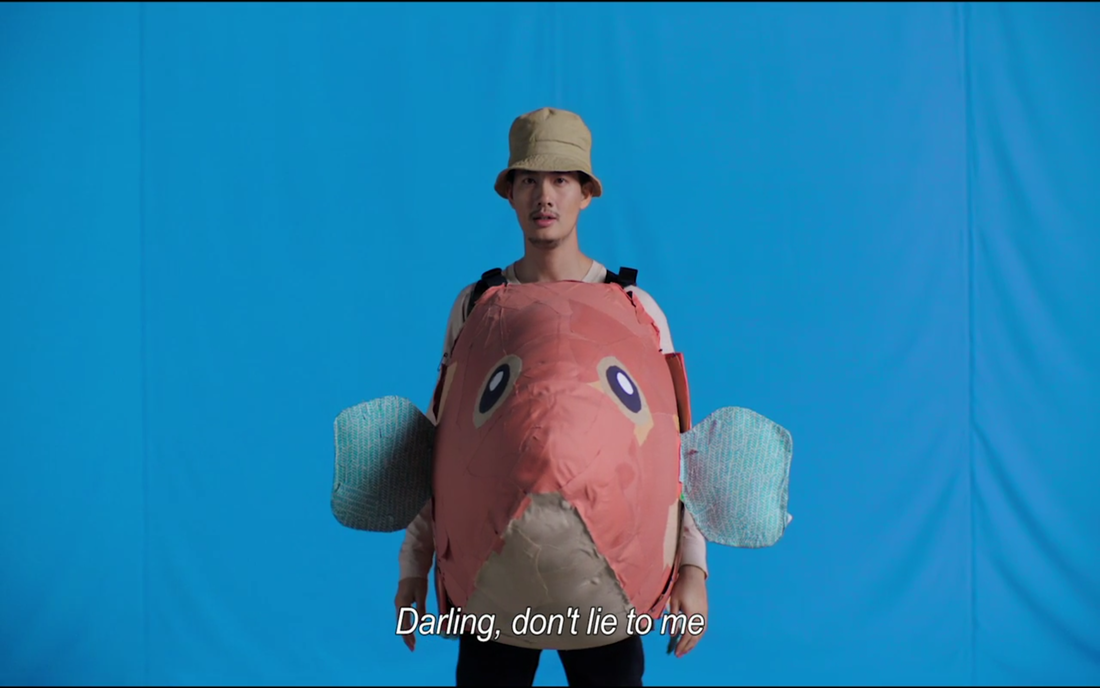

Without wanting to rush comparisons (Rohrwacher's genre is in a league and style of its own, deserving of every award), I was struck by the way it shared thematic commonalities with another recent Italian film, Michelangelo Frammartino's Il Buco. In VERY different ways, both films are about the landscape, an encounter with nonhuman lives and entities. In both, there is this desire to descend into earth itself, and therefore plunge the viewer into various paradoxes of seeing and not seeing. And both feature a magical fable-like quality, including a non didactic 'lesson' at its heart: in La Chimera, this might be the refrain that the votive objects found in the old tombs are 'not meant for human eyes'; in Il Buco, as the explorers descend deeper and deeper into a subterranean cave, mapping every crevice, a local farmer becomes progressively more ill.

There is a kind of magic here, and a vital, poetic cosmology, both earthly and invisible. Our lives only make sense to the extent that they belong to the land.

And the threads that bind us to earth may be frayed and broken, but lo, they persist.

Glad to be around as these films are being made.

(Images: above, La Chimera. Below, Il Buco)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed