Jay plays a small role, as part of a gang of suave confidence tricksters, or con men. He first appears, and this really is his scene, sitting at a poker table, engaged in a fraught high-stakes game. He ends up winning the last round, but things turn nasty when it transpires the game's main loser doesn't have the requisite cash. However, just as Jay's character pulls out a gun out and places it menacingly on the table, the film's protagonist, a psychologist, who has been observing the game all along, offers to step in to cover the missing money. The psychologist signs a cheque, but just before handing it over, spots a few drops of water seeping out of the gun, prompting her to refuse handing over the money; instead, she makes a comment about the nonthreatening water pistol is. In response, Jay's character and the other card players suddenly stop their act: it transpires that the whole game was merely a set up, a con, to trick the psychologist out of her money. She initially fell for it, and so did we, as film viewers.

What's memorable about House of Games is the way this scene, which occurs towards the beginning, establishes much of the the premise of this film about cons (and about cons within cons).

Without spoiling the plot if you haven't see it, I can say that it's a film that gives the viewer the key for unlocking the film from the very beginning. This is quite different from magic-themed films such as The Prestige or The Illusionist, which use a Sixth Sense-like approach of fooling the viewer right up until the final twist: in these films there is always the "ooo" moment at the end, where you realise it was all staged to to make you believe in a very different reality than the one you've been following all along. It's a kind of 'who dunnit' structure, operating at the level of the whole narrative: and so it turns out, for instance, that there were really two identical twin magicians all along, or that the main character's love interest had only pretended to die, etc.

In House of Games, after the Ricky Jay scene, we are invited on a similarly deceptive narrative journey, except that here we have been clearly told that this will be the case, and shown exactly the mechanics at play (unlike in The Prestige and The Illusionist). The initial Poker-playing scene is there to tell us: "See, this is how a con is done. These people are pretending, they are 'acting' as though there is a gun, a threat, real money. You have been warned..."

The film treats us, its audience, with respect. It grants us the intelligence to be able to see through the illusion, and to then appreciate it as such. It doesn't just fool us. It first tells us, and shows us, exactly how it's going to fool us; and then it does it.

And this is such a valuable model for magic and magicians. For thinking about a magician's relation to the audience: do you merely show them something amazing and unexplainable? Or do you let them in on the dynamic of illusion and magic (without spoilers), and then proceed to do illusion and magic?

PS The 'note' I mentioned at the top has to do with the gender dynamics in the narrative, which are a little let's say "dated" (read: chauvinistic male fantasy). There is a theme of 'loving your captor' underlying much of it, and the captive is a woman. That said, there is much appreciate here that doesn't rely on regressive gender politics.

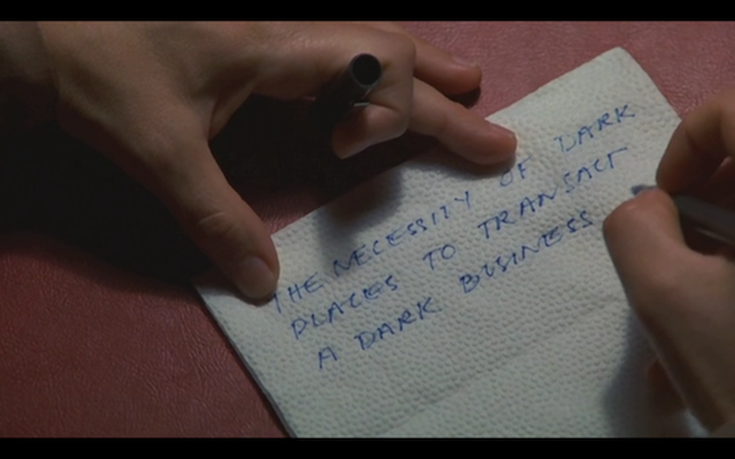

PSS On an unrelated note, I love this sentence that the protagonist writes on a bar napkin, after she returns to the dingy bar: 'The necessity of dark places to transact a dark business'.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed